Stories

Klaus’ Corner: Skiing in the Age of COVID-19

Those who know our co-founder Klaus Polzer know that he's an endless fount of information—not just about skiing, but the world in general. If you’ve got the patience to sit still and get "Klausified," you're bound to learn a thing or two.

With almost all ski resorts worldwide shut down and the spring touring season up in thin air, you’ve probably been wondering: is it a good idea to go skiing? In his first semi-regular column on our website, Klaus dishes his two cents on skiing in the age of COVID-19—and goes deep on why it's so hard, even for the scientists, to know what will happen.

As a ski-focused publication, it’s anything but simple to write something sensible these days. The world has changed tremendously over the past few months, and with every new development, our passion for sliding around on two planks seems to slide farther into temporary irrelevance.

The last lift operations in the Alps closed around mid-March, and even the few countries that kept their ski resorts open after the onset of the new coronavirus in Europe—Sweden and Russia—have officially ended their ski season by now. When I first heard that ski areas were closing, I thought: “No problem, this leaves more options for ski touring.” Then the restrictions on travel came, and some countries even banned people from leaving their homes unless absolutely necessary. That changed my mind about touring.

It wasn’t an easy decision. At first, I thought: “What’s the problem? You can’t catch or spread the virus if you’re ski touring alone in the mountains. It’s a perfect time to skin up!” Then it occurred to me that I was likely not the only one thinking this way, and that this could cause problems. After pondering it some more, I realized that I shouldn’t go ski touring—or engage in any sort of potentially risky activity just for fun. These are times when the infrastructure of most countries, particularly health care resources like hospitals, doctors, and even mountain rescue (which is currently helping in the valleys), are under permanent stress. The last thing anyone needs is people hurting themselves while charging down a mountain or getting buried in an avalanche.

So, a request from my side to our readers: Please think twice before going skiing! And please also refrain from communicating in ways that may incite others to go skiing. Should we stop thinking about skiing altogether? Hell, no! Surely, we can think and dream—and of course we’ll continue to post on Downdays—but it should be clear that we won’t be able to actually be doing any skiing responsibly in most places, at least for a while longer.

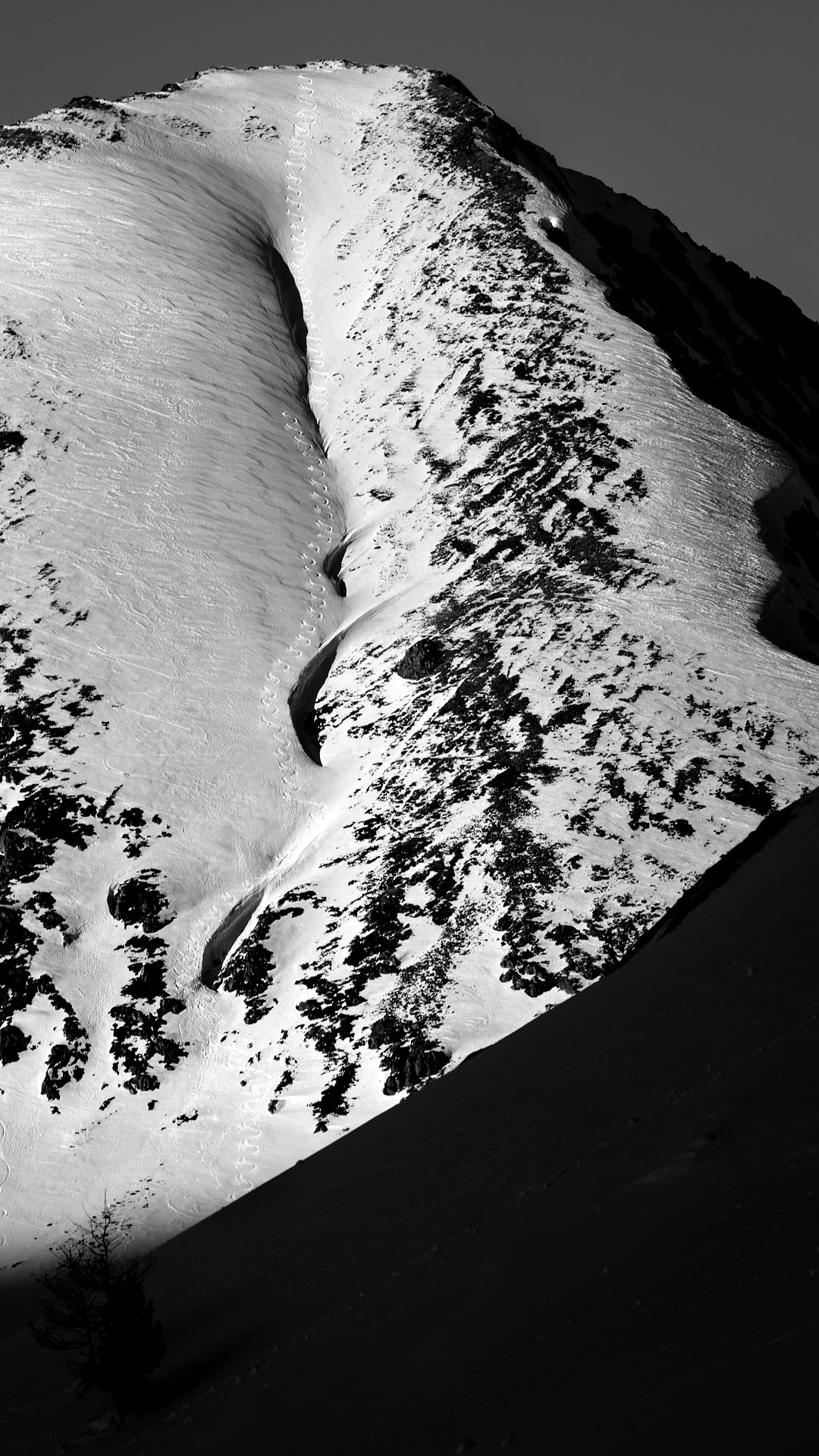

This what you´re wanting? You may need to wait a while longer.

The Counter-Argument

Some might argue: "If life is running as usual where I’m at, what’s the problem with going skiing?" Some will also point out: "It’s more dangerous to stay inside all the time and not move at all!" To address the second point first: Obviously, you should go out to practice some sports if you’re allowed to. But my suggestion is to stick with sports you can do alone, in the vicinity of your home, and that are less dangerous than skiing. If you happen to live next to a ski hill and skin up the piste as an endurance practice, I’m not talking to you, although you should still take it mellow on the way down. A backyard rail set-up? Though within the realm of possibility, it might be more questionable—the main goal being to exclude the possibility of a hospital visit.

Addressing the first point is a little more complicated. Sweden obviously applied a different strategy than the rest of Europe in allowing resorts to remain open, as did countries in Asia, and according to current numbers of deaths, these countries are still doing okay—although all these countries have resorted to more stringent measures of social distancing over time, and numbers of recorded infections and COVID-19 related deaths are still on the rise. Whether or not they are doing the right thing, nobody knows for sure. And I mean, really, nobody. (I'll expand on that further down.)

Given that there's still a lot we don't know, I think the only viable way to go is to do everything reasonably possible to avoid getting to the place that parts of Italy, Spain and the US are already at: the point where people are seriously ill—be it from COVID-19 or any other disease—and can’t receive the necessary medical treatment because there are too many in need. In my book, not going skiing counts among the measures that are reasonably possible, and a small price to pay for staying on the safe side.

Somewhere out there, a spot is waiting for you to hit it—when the time is right.

What We Know vs. What We Don’t

If you just want to read about skiing, you might want to stop here. As I mentioned above, I’m going to expand a bit on the current “coronavirus situation.” I don’t want to judge any country, measure, person or opinion. But I do want to highlight the simple fact that our knowledge in respect to SARS-CoV-2 (the official name of the virus that causes the disease COVID-19) is still rather limited.

This shouldn’t surprise us, since the whole topic is still new in the framework of science and the acquisition of human knowledge. Everyone even slightly involved in science knows that the time scale for scientific progress is usually measured in years, not days. Nevertheless, the constant stream of news we see today implies that we know a lot about what’s going on. Yet what we’re seeing is only part of the picture.

To provide an obvious example: almost every media mention of the numbers of infections with SARS-CoV-2 refers to one of several popular “virus trackers” like that of Johns Hopkins University. These are great tools, but—as is clearly stated—they track only confirmed infections. This is an entirely different measurement than the number of actual total infections per country or region. It’s also a number with varying value for different countries, since almost every country has a different capacity of performing tests as well as a different testing strategy. To make things even more complicated, the usual testing methods don’t clearly detect every infected person.

It may be convenient to compare numbers from different countries (as is done here, for example) but it’s a risky business to draw any conclusions without taking into account the different underlying processes of compiling these numbers. Which organs or agencies are capable of performing this task at a glance, even within the scientific community? It is more important now than ever when we see some piece of information—an article on a website or a post on social media—that we carefully evaluate the source and the context of that information. Is someone comparing apples with oranges? Is that quoted scientist a real scientist? Where are they working, and have they published any well-respected studies or articles before? In the age of Google, these are things that everyone can easily find out—if they care enough to do the extra work.

Tools We Need

But let’s get back to our problem: the "coronavirus situation." I think everyone can agree that we want to have as little restrictions in our lives, together with the best possible health care. How to achieve that is the big question. I'm afraid that nobody can answer this question at the moment—not even a collective of all the best scientists in the relevant fields. We simply lack the right information and the right tools.

The good news is that we’re gaining more insight by the day, and it looks like we'll get some valuable new tools soon. Among the first will be reliable, fast and cheap tests on whether someone is newly infected and whether someone's been infected in the recent past, but has recovered and is now immune (those are actually two very different tests). Firstly, this will allow us to gain more knowledge about how many people are really infected, which populations are more heavily impacted, how long will people be immune after a recovery, and so on. Secondly, it will allow us to more efficiently separate infected people, without the need to shut down contact between people entirely.

The second tool we can hope for is a treatment for the COVID-19 disease. Ideally, that's a drug that is already approved for other diseases, since that would speed up the process drastically. The treatment doesn't need to be perfect; unfortunately, our treatments for viruses are rarely as effective as our antibiotics are against germ agents. But if it can lower the lethality a bit and shorten the time that heavily affected patients will require intensive care in hospitals, it will help a lot. This treatment might take longer to materialize than improved tests, but there’s hope that we will see positive developments in the next few months.

I think everyone can agree that we want to have as little restrictions in our lives, together with the best possible health care. How to achieve that is the big question.

The REAL Problem

The bad news is that the ultimate tool that we need—a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2— will probably take at least another year until it’s widely available. What does that mean? It means that we can hope for a gradual change for the better—meaning a somewhat stable situation in the medical sector and fewer restrictions for general society. But it also means that the virus will continue to have a significant effect on our lives. It seems pretty clear by now that strategies that aim for herd immunity don’t work without severely overstressing health care systems. Therefore, containment of SARS-CoV-2 until we have a vaccine is the only possible way to go.

We are now entering a phase where social distancing measures have stopped the exponential spread of SARS-CoV-2 in many countries, and the debates are heating up on whether, and how, those measures of social distancing should be reduced. For skiing, this debate has no immediate relevance, since any changes will be too late for the current season—barring perhaps a few glacer resorts. But it’s very likely that we will still be seeing similar debates by the time the next ski season rolls around.

There’s an interesting analogy between the situation many governments are currently facing as they consider reducing social distancing in order to revive the economy and social life of their countries, and a situation that every backcountry skier is familiar with: the decision whether to ski a slope in the face of avalanche danger. In both cases, it’s impossible to have perfect information; you simply can’t be 100% sure about the results of your decision. In both cases there’s a tempting reward—accompanied by a potentially devastating punishment if things don’t go your way.

It´s a general rule of thumb not to drop in if you don´t know what you´re getting yourself into.

As skiers, we can improve our decision-making in the above scenario by increasing our knowledge: both general knowledge about how avalanches work, and specific knowledge about the slope’s snow cover using sources like avalanche and weather reports, or by digging a snow pit. If we’re lacking in knowledge, the only sensible thing to do is to skip the slope and stay safe. If it’s general knowledge we’re lacking, maybe we should hire a guide or take a course. If it’s specific knowledge, better look up the avalanche report next time and learn how to interpret a snow pit.

In this analogy, the challenge facing governments becomes clear. Skiers have a wide variety of resources available to improve their knowledge and inform their decision-making. Governments managing their response to the virus don’t. It’s like being dropped off on top of a backcountry line in some distant part of the world, where you have no experience about weather patterns and snowpack history. Of course, you can make do with the prior experience that you’ve got, combined with onsite observations. This is exactly what scientists around the world are doing now with SARS-CoV-2. But it will still take a while until they can accumulate enough data about the virus to inform their decisions with the same reliability that skiers have grown accustomed to, in the context of weather and snow data, to inform theirs.

Another problem is that most countries still lack the right safety equipment; they’re in the backcountry without beacons and airbags. In the case of Covid-19, this equipment includes efficient widespread testing, ventilators and tracking resources. As for now, I think the only thing governments can do is attempt to mitigate risk by gaining both knowledge and equipment, ASAP. Let’s hope that they hire the right guides—scientists, that is—and don’t fall for the sweet temptation of a perfect-looking line that may or may not rip out underneath their feet.

To drop in or not? It depends on the information you´ve got, its reliability, and the amount of risk you want to take on.

Math Class

Finally, I'd like to provide a little background to my thoughts. If you're still with me and feel inclined, get ready for a little math. Basically, every growth of a population—and the spread of a virus is nothing else—can be graphed as a logistic function. It starts with an exponential phase, then grows almost linearly for a while before approaching its logarithmic maximum. There’s one very important number in this function: the logistic growth rate, which determines how steep the curve gets. In our case the growth rate is influenced by many different factors: how efficiently the virus is passed from one person to another, how long a person is infectious, how often an infected person is in contact with non-infected people, how many different people an infected person contacts, how close the contact is, and so on. Obviously, it’s almost impossible to calculate this growth rate exactly given so many influencing factors—which even include the weather. This is just one reason why modeling the evolution of any epidemic, and this one in particular, is tricky business.

One thing we know from the curve of the log function is that as the growth rate diminishes, the exponential phase of growth becomes less prominent and growth becomes more steady in general. The downside is that more time passes before reaching the upper limit—that’s when most people have been infected and recovered already.

What’s the best overall strategy? As long as we don’t have an effective vaccine, we should aim to make the curve as steep as possible, without surpassing the capacity of our medical sector. Here, yet another factor comes into play: of all infected people (not to be confused with all confirmed infected people), how many get so seriously ill so that they need treatment in a hospital?

Treatment over time

Just in case you didn’t have enough factors to consider, here's one more: How long do infected people need hospital treatment? Obviously, people who get infected aren’t sick forever; they fall out of the reservoir of people whom the virus can infect (depending, of course, on how long someone will stay immune after recovery). Luckily, most will recover in a few weeks. Assuming that the percentage of people who get seriously ill remains constant, ultimately the number of people we can allow to become newly infected over a certain period of time is determined by the time that patients need to spend in the hospital before they recover. I am speaking of an average here, and I am also assuming the phase of rather constant growth: one person recovers, the next one gets ill. That’s why an effective treatment would help a lot; if people recover more quickly, we can allow for more infections over time in general.

So here you have it: a simple (or not) picture of why we do not—indeed, cannot—know yet what to do. There are simply too many things we don’t know yet, since we don’t have the tools yet to gather the necessary data (like more efficient and widely available tests). Of course, the real model that will advise us of what to do will be much more complicated than all the factors I’ve touched on. But I’m optimistic that our scientists will be able to handle it once the necessary information becomes available.

In The Long Run

What does all this mean longterm? As I mentioned before, it looks like we'll be dealing with SARS-CoV-2 for quite a long while, and our only way out of the current situation will be a vaccine. Even the current, seemingly huge numbers of reported infections and deaths in countries like Italy, Spain, and the USA are still small in relation to the total population. Spain currently has the highest number of deaths per capita, but it’s still highly unlikely that more than a few percent of the total population have been infected yet with SARS-CoV-2. The exact number we just don’t know, as I hope I made clear above. This means that even a country that’s been among the hardest hit so far could still be in the phase of exponential growth, if it wasn’t for the strict social distancing measures currently in place.

As a consequence, social distancing will remain relevant until we have a vaccine—likely for another year, at least. Obviously, this includes the next skiing season. Does that mean that we will miss another winter on skis? I don’t think so. Of course, skiing will look differently than in the recent past, particularly in respect to mass tourism. How it all will play out remains to be seen. At the very least touring will be an option next winter, and who knows—maybe we’ll see a revival of low-profile ski areas with two-seater-chairlifts. Last but not least, people might actually start behaving like civilized beings in the lift line. Doesn’t sound too bad to me!