Stories

Climate Change and the Future of Ski Resorts

Words: Jaakko Järvensivu

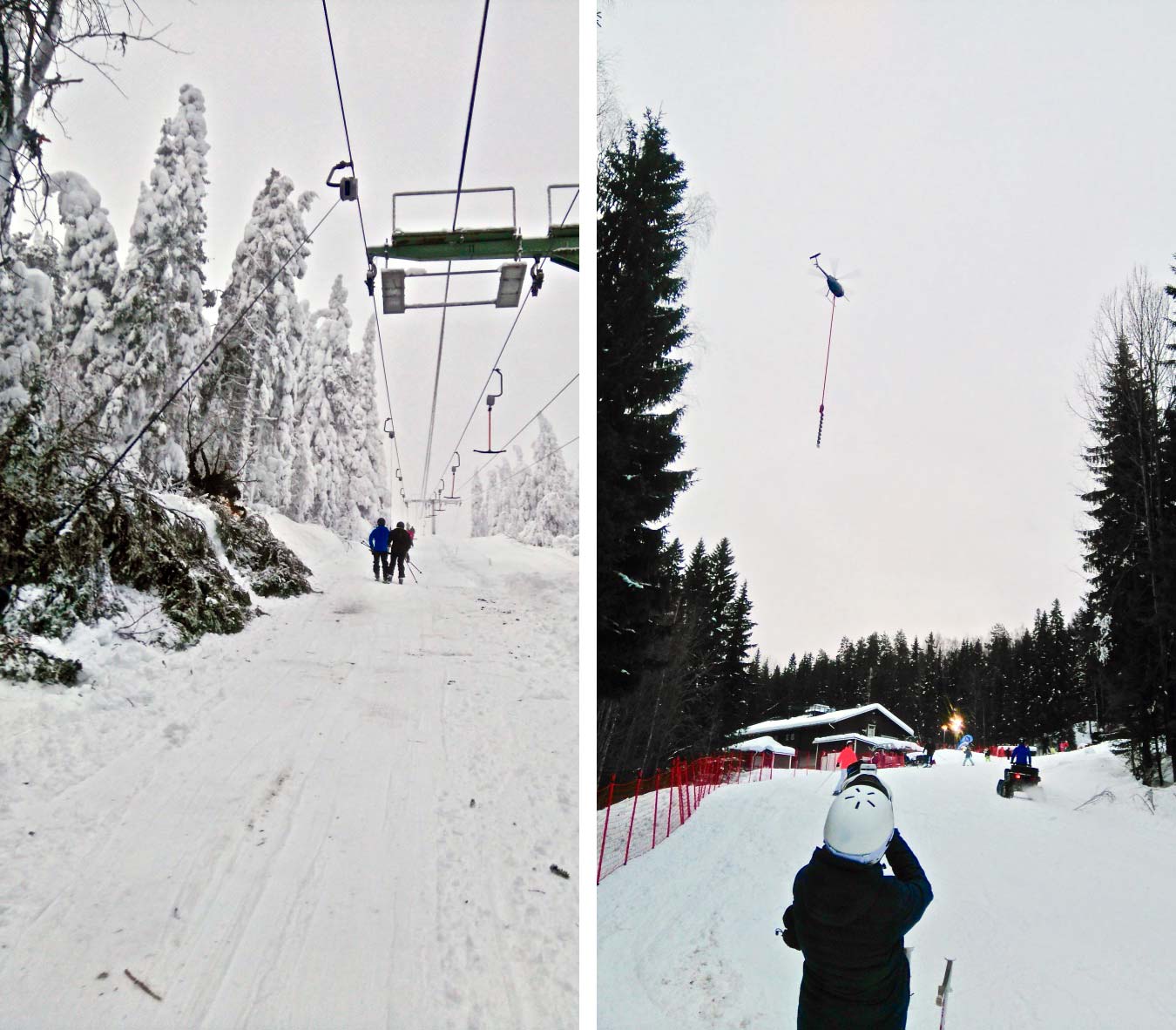

28 December 2017: Koli National Park, Finland

It should be a busy ski day after the Christmas holidays, but the lifts and cross-country trails remain closed. The Koli ski resort has given an official warning to stay out of the surrounding forests due to the heavy loads of frozen snow in the trees. Aided by gusty winds, these icy masses could come plummeting down at any time, bringing huge branches or the whole tree with them. The wet snow has accumulated during heavy snowfall in the past few days. A prolonged period of warm weather has added to the problem, with permafrost melting affecting the top layer of soil where the tree roots keep their hold.

The freak weather phenomenon has wreaked havoc. Upon my arrival in the area the day before, parts of the municipality of North-Karelia in eastern Finland had already been cut off from electricity for over 48 hours due to trees falling on electricity lines, affecting the lives of nearly seven thousand people.

The following day, the ski resort opens one of the lifts. While we wait in the lift line, a helicopter dangling a circular saw blade on a steel cable flies overhead. It hovers over the chairlift, cutting threatening branches from the side of the lift line on its way up the slope. In my thirty-plus years of skiing, I’ve never seen anything like it.

Koli, Finland in December 2017. Photos: Jakko Järvensivu

Climate change has already made unusual weather phenomena like this almost everyday news, and failing to address the problem could change skiing as we know it. Human-caused emissions have already warmed the climate by one degree since the start of modern industrialism in the mid-1800s, and in the Alps and parts of Scandinavia it has already warmed by two degrees.

According to NASA, the pace of warming has quickened dramatically in the last 35 years. The five warmest years on record all took place after 2010, and 2016 was the warmest recorded year ever. Glaciers in the Alps have already lost 30 to 40% of their area, and one half of their mass, in the years between 1850 and 1980; since 1980, another 10 to 20% of the ice has disappeared. The hot summer of 2003 alone accounted for a 10% loss of the remaining glacier mass. It’s estimated that by 2050, around 75% of the glaciers in the Swiss Alps will disappear. In Scandinavia, researchers studying the Hardangerjokulen glacier in Norway estimate that the ice cap, which is 300 meters thick in places, may disappear before the end of the century if the warming trend continues.

Snowfall levels in the French Alps dropped an average of 64 centimeters between 1960 and 2007. According to recent studies, the Alps could lose nearly 70% of their yearly snow cover by the year 2100. Given current emission levels, temperatures in Finland will rise by five degrees Celcius in the summer months, and eight in the winter months, within the next 100 years. In Switzerland, given a high-emissions scenario until 2050, temperatures will rise between 2.5 and 5 degrees by the year 2085.

FUTURE SNOW RELIABILITY

Today, we are used to skiing on slopes with excellent snow conditions, and we expect a months-long ski season in return for our investment in a ski pass. In the future, we may have to be willing to lower our standards, as global warming makes it more difficult for resorts to guarantee snow reliability.

Researchers have commonly defined a resort to be “snow reliable” if it can provide a continuous 100-day ski season, with at least 30cm of snow on the slopes, in seven out of 10 seasons. In the late 1990s, this was possible in the Alps with natural snow in areas above 1200 meters of elevation. This level is expected to rise to a minimum altitude of 1500 meters with a warming of two degrees.

“Just a snowball’s throw from the legendary Kitzbühel, the SkiStar St. Johann Ski Resort makes for amazing family vacations,” proclaims the introduction to the resort of St. Johann on the website Tyrol.com, followed a few lines later with the reassuring statement: “Well known for reliable snowfall and consistently good snow conditions.” However, considering St. Johann’s low altitude, with a top elevation of 1605 meters, the snow conditions here might be less assuring in the future.

St. Johann was one of three ski areas researched in 2010 by Austrian climatologist Robert Steiger. His study revealed that, using the 100-day indicator for snow reliability in a high-emission scenario, the region’s snow-secure ski terrain would diminish by around 50 percent by the 2050s, and by 90 percent by the 2070s. A later study that included all the ski areas in the Tyrolean Alps reported similar conclusions given a high-emission scenario: only 50 percent of the resorts in the region will be snow-reliable in the 2070s. Towards the end of the century, the number declines to a stunning 15 percent.

With a top elevation of 1605 meters, the ski resort of St. Johann in Tirol may no longer be snow-reliable by the middle of the 21st century. Photo: Kitzbüheler Alpen

In 2007, it was estimated that 91% of the nearly 700 ski areas in the Alps were snow-reliable, according to the 100-day indicator. In a two-degree warming scenario, that number drops to 61% (about 400 snow-reliable resorts), and with a warming of four degrees, to only 30% (about 200 snow-reliable resorts).

Ski resorts in Germany are among the most vulnerable to warming, due to the low mean altitude of the Bavarian resorts. A +1°C warming scenario would lead to a 60% decrease in the country’s snow-reliable ski terrain. With four degrees of warming, Germany would have only one snow-reliable ski resort left. Germany is closely followed by Austria, where around 40% of the resorts are situated at a mean altitude of less than 1300 meters. Ski resorts in France and Italy are situated roughly on an Alpine average, while Switzerland, thanks to its high-alpine resorts, is the least affected by warming.

Even in Switzerland, there are lower-elevation resorts already feeling the effects of climate change. The Oeschinensee-Kandersteg ski resort, around 60 kilometers from the government seat in Bern, has four T-bars, one gondola and a top station at 1680 meters. The small family resort is situated in the Bernese Oberland, an area that, according to an OECD report, will be the most affected by climate change in Switzerland. The report estimated in 2007 that only half of the current ski slopes in lower-lying regions, including those in central and western Switzerland, would be naturally snow-reliable with a 300-meter rise in the snow line. A quick Internet search reveals more than 50 resorts in these regions with a top lift elevation of 1500 meters or less. According to the national weather service MeteoSwiss, the zero-degree line in Switzerland, which currently resides at 900 meters, will rise to 1500 meters by 2085 in a high-emission scenario.

Some studies have estimated that the high altitude of many ski resorts in the French Alps could help the region’s resort to continue profitable operations into the 2030s with relative ease. Not all of the country’s ski areas enjoy a high altitude, however. One such resort is Abondance in the Haute Savoie department. Part of the Portes Du Soleil ski area, the resort was reported as the first ski-area victim of climate change when it closed down its lifts during the 2006/2007 season after more than four decades of operation. The lift company reported losses of more than 600,000 euros due to a bad snow year, which forced the city council, representing the town’s 1300 inhabitants, to close down the operation.

With the top lift at 1730 meters, most of Abondance’s ski terrain falls in the range of 900-1500m—elevations which, according to researchers, have seen the largest snowfall declines in recent history. Still, failing to invest in a snowmaking system may have played an even larger role in the resort’s problems. Abondance reopened for the 2009/2010 ski season and has remained open since, despite still relying on natural snow. Of the 37 resorts in Haute Savoie, 11 have a top lift elevation of no more than 1500 meters. Météo-France predicts that temperatures in the French Alps will keep rising until the 2050s, regardless of any climate countermeasures that are taken.

A ski class at Abondance, one of many lower-elevation resorts already feeling the effects of climate change. Photo: Abondance.org

Small, lower-elevation resorts across the Alps will be among the first to suffer from climate change if we cannot lower our CO2 emissions considerably and quickly. While these family resorts might not be economically among the most important ones, it’s these familiar, inexpensive ski areas, with easy access from nearby cities, that have traditionally offered the first skiing experiences for generations of skiers. Without these feeder resorts, skiing would be far less accessible for future generations, hastening the descent of the already declining number of skiers. With fewer resorts to choose from, the skiers who stick it out will have to be willing to travel longer to higher-altitude resorts, pay more for their lift tickets and endure bigger crowds—both while traveling and on the slopes. Some regions that have traditionally depended on winter tourism will have to find alternative ways of attracting visitors in the winter season, and develop their summer tourism offerings.

ECONOMIC EFFECTS

The precarious future of skiing and ski resorts implies significant economic effects, not just for the world’s ski centers, but for tourism regions and even whole countries. Around 60 to 80 million people visit the Alps every year, and tourism activities in the area provide 10 to 12% of the jobs while generating close to €50 billion annually. By the numbers, France is the leading Alpine country, with more than 300 resorts that account for a third of the skiing terrain in all of Europe. France also records the most average skier days, with 54.9 million per season.

Winter tourism is the most important income source in many parts of the Swiss Alps, and accounts for 4.5 percent of Austria’s GNP, around half of the country’s total tourism sector. In Scandinavia, tourism in the Finnish Lapland alone accounts for €1 billion in annual revenue—most of which comes from winter tourism—and is a major employer in an area with a 13% unemployment rate.

Climatologists predict that future temperature rises will be the strongest during the early months of the season, from November to January. A 2013 study by Steiger and Johann Stötter found that less than half of the resorts in the Tyrolean Alps will be snow-secure during the Christmas season in the 2040s, given current CO2 emission levels. Moving towards the end of the century, the number declines to under 10%.

The Christmas season is extremely important to ski resorts in the Alps. It’s been estimated that around a third of the season’s profits are made during the two-week holiday season. Resorts in the Alps could experience crucial loss of revenue with deteriorating early-season conditions.

In Scandinavia, early-season warming is already evident. In order to open in November or December, resorts in the southern regions now use snow guns whenever possible.

“Now we have to make snow for a day or even just for half of the day, says Pekka Markkanen, manager of Messilä ski resort in Lahti, Finland. “In the old days, this would have been unheard of.” According to Markkanen, setting up and dismantling the equipment is the most expensive part of snowmaking. The general cost of snowmaking in October is €30 per cubic meter, compared to €1 per cubic meter in January, according to a recent study in Lapland.

In Finnish Lapland, December accounted for the most overnight stays of any month in 2017, with nearly half a million recorded visitors. Of course, Lapland has attractions beyond skiing: most Christmas visitors are drawn by the aurora borealis, snowmobiles, huskies and reindeer safaris. Nevertheless, visitors come expecting snow and cold weather, and the southern parts of Lapland have already experienced difficulties, such as the bad snow years of the early 2000s.

It’s already clear that skiers will need to get used to the fact that ski seasons will start later in the year, and the chances of being able to ski over the Christmas holidays in the Alps and southern parts of Scandinavia will get even smaller over the next decades.

With a base at 1440 meters and top elevation of 2,961 meters, Andermatt in Switzerland is an example of higher-elevation Alpine ski resorts that, in the short term, will be less affected by climate change. Photo: Järvensivu

CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION

For resorts, climate change is a question of survival: they have to make the right decisions now to keep the lifts running in the future. With no magic crystal ball available to tell exactly how climate change will proceed, climate simulations provided by meteorological institutes provide one of the best platforms to base decisions on.

Andrea Damm, of the Austrian Joanneaum Research Institute, worked on a European Union-funded project investigating the market for climate services, and how ski resorts and other entities can benefit from the use of climate information. A 2018 study of which Damm was part determined that the use of climate services in Austria was still limited, partly due to low risk awareness and even risk denial. Still, there is evidence of change.

According to Damm, one ski resort in Austria has already made major business decisions based on such data: a resort called Annaberg, situated in eastern Austria, decided to close some lower-lying parts of their ski slopes and move the snowmaking system to higher areas after seeing the findings of a study they’d had done in 2016. Damm says that risk awareness is currently more present among smaller, lower-lying resorts in eastern Austria for a simple reason: “They already feel the effects of climate change.”

Resorts with a top station situated above 2000 meters will survive, and lower [ones] have to refocus themselves, find something new.

In Scandinavia, the situation has not yet escalated to be the defining factor in companies’ investment decisions, according to Damm´s colleague, climate risk researcher Atte Harjanne of the Finnish Meteorological Institute in Helsinki. “In Lapland, the tourism industry has grown so much during the last few years, and the resorts in the south live hand-to-mouth,” says Harjanne. “What happens in a decadal time scale does not define the action.”

It’s clear that the altitude of ski areas in the Alps will play a significant role in their future survival. Even Swiss banks currently give only very restricted loans to ski areas at altitudes below 1500m. But rather than the decline of natural snow, it is the changes in temperatures suitable for snowmaking that will have the greatest effects, as many ski resorts have been dependent on artificial snowmaking already for decades.

A 2008 study by Steiger and Mayer defined the technical snowmaking limit in the Alps as 1000 meters of elevation. This limit was estimated to rise to 1600 meters if temperatures rise by two degrees. Harjanne is skeptical on the chance of holding temperature rise to two degrees, while Daniel Lüscher from the Swiss organization myblueplanet puts it even more bluntly: “Resorts with a top station situated above 2000 meters will survive, and lower [ones] have to refocus themselves, find something new.” This will have serious consequences for the quarter of Alpine resorts that are situated under 1200 meters.

Even resorts with high-elevation terrain will still be affected if the ski village is situated on the valley floor, which is often the case. The top station of the Aiguille du Midi at 3842 meters, which gives access to the famous Vallée Blanche ski route, may be the highest ski lift in Europe—but being able to ski all the way back to the town of Chamonix at 1035 meters could become a rare event in the future.

The receding technical snowmaking line could close many small local areas in the Alps, while increasing the market share of bigger ski areas at higher elevations. However, could it also offer some small ski areas a chance to return to the roots of skiing, before the dawn of mass tourism? Along with the rising popularity of ski touring, the changing market may offer opportunities for down-scaled eco-tourism, which showcases local produce and culture in a manner not possible in a modern megaresort.

One example of such a move is the ski resort of Gschwender Horn in Immenstadt, Germany, where the municipality decided to close the ski resort after a series of bad snow years in the early 1990s. After dismantling the lifts and re-naturalizing the slopes, the area now serves as a base for year-round outdoor activities such as hiking, mountain biking, snowshoeing and ski touring.

The former ski resort of Gschwender Horn above Immenstadt, Germany. Photo: Wikipedia

INCREASES IN SNOWMAKING

Global warming is forcing ski resorts to invest heavily in modern snowmaking systems in order to guarantee long ski seasons with adequate snow conditions. The ski resort in Ruka, Finland has already invested millions of euros in the development of its snowmaking technology and capacity, according to local manager Matti Parviainen. Parviainen says this development will continue in the future: “It doesn’t stop here. It’s ongoing renewal of the equipment.”

A 2013 study in Austria found that in order to sustain a 100-day ski season, half of the ski resorts studied in the Tyrol region would have to double their artificial snow production by the 2050s in a high-emission scenario. This, of course, means significant rises in yearly snowmaking costs. The resulting increases in lift ticket prices could make skiing an even more exclusive sport.

Improvements in snowmaking will enable resorts to keep going until they reach an economic threshold, after which the operation will no longer be profitable. This point will be reached when the required investments in snowmaking have become be too great, the days when snowmaking is needed too many, and days suitable for snowmaking too few.

When exactly this threshold will be reached will vary, depending on a ski area’s altitude and location, future CO2 emission levels, the financial resources available, and the public’s willingness to tolerate both deteriorating skiing conditions and rising lift ticket prices.

As climate change progresses, it may also have effects on our habits of consumption: more ecological hobbies or ways of traveling may gain in popularity.

One alternative for the future for ski resorts will be increasing the offer year-round activities that aren’t dependent on snow. According to Lüschner from My Blue Planet, mountain regions in Switzerland are already focusing on summer with new programs and activities. The number of mountain-biking trails and activities is increasing, both in the Alps and Scandinavia. Harjanne sees year-round activities as a good adaptation method for ski resorts: “It balances the activity and makes it less dependent on winter and snow.”

Kitzbühel, October 2018. Photo: Andreas Schrämbock

PREVENTIVE MEASURES – TOWARDS A CARBON NEUTRAL SKI RESORT

Climate simulations indicate that warming will continue until the 2040-50s regardless of any actions taken, but the decisions we make now still have a great impact on the last part of the century. If, for example, global warming can be contained within the two-degree goal set by the Paris Climate Convention, only 30% of snow cover in the Alps would be lost, with 60% of the area’s resorts remaining snow-reliable. (Compare that with the 70% snow cover loss and 30% snow reliability predicted at current emission levels.) Reaching that goal won’t be easy, and will require new ways of thinking and difficult government-level decisions. In the bigger picture, the choices made by companies and consumers will also have an effect.

SCANDINAVIA

“It’s important that we do not blame people who are only in the beginning of the path,” says Niklas Kaskeala, chairman and founder of Protect Our Winters Finland. “A big part of our message is that you can start by taking small steps.” Started in 2007 by American pro snowboarder Jeremy Jones, POW is a grassroots organization focused on influencing the entire winter sports community, from ski resorts and gear manufacturers to athletes and individuals, to make more climate-friendly decisions.

In 2016 the group launched an eco-electricity campaign in Finland, which resulted in five resorts certifying their electricity as ecologically-produced. In 2018, they’ve focused on promoting climate-friendly food. The campaign includes vegetarian recipes from athletes like Olympic-medalist snowboarder Enni Rukajärvi, and special grocery bags filled with climate-friendly food that can be purchased in ski-resort grocery stores. POW Finland has also created “a path to save winters,” where skiers and snowboarders are advised on a step-by-step basis about how their individual choices can make a difference. The path recommends taking a stand on climate change, trying to influence your friends, and even engagement in political action.

It’s important that we do not blame people who are only in the beginning of the path. A big part of our message is that you can start by taking small steps.

Pyhä, a POW partner resort in eastern Lapland, is the first carbon-neutral ski resort in the Nordic countries. According to Jusu Toivonen, who started the environmental program in Pyhä in 2008, one of the first steps was to start using electricity made from 100-percent renewable sources. The resort then joined the E.U.’s energy efficiency contract, which involved a decrease of overall energy consumption. Toivonen says the process made the resort analyze its energy consumption, how much total energy was consumed, for example, by snowmaking and slope-grooming. One result was more ecologically minded procedures for snowcat operation.

Another way to cut down energy-intensive snowmaking was better usage of snow fences, which Pyhä studied together with the University of Applied Sciences in Rovaniemi. Toivonen is pleased with the results. “We have developed the snow fences a great deal during the past five years,” he says. “Now we can gather a lot of snow with them every time it snows and is windy.”

Pyhä currently relies on hydropower for electricity and a woodchip-fueled district plant for heating. The resort also compensates the CO2 emissions caused by slope grooming with donations to WWF-supported renewable energy projects.

Toivonen thinks that global warming has already made predicting the climate in Lapland difficult. “You can all of a sudden have +5°C and rain in the beginning of January, and then have -30°C the following week,” he says. Toivonen thinks that ski resorts have a moral responsibility to operate ecologically. “We’re living off snow and winter, so I [think] it very odd that you would use coal power,” he adds. He hopes that the issue will be addressed more openly in the ski industry. “It’s been organizations such as POW that have been pushing resorts forward,” he concludes.

Pyhä, Finland. Photo: Järvensivu

THE ALPS

I Am Pro Snow is part of the Climate Reality Project founded by Al Gore. Like POW, the organization seeks to motivate the winter sports community into action on climate with initiatives like their “100% Committed” campaign, which encourages individuals and companies to begin using 100% renewable electricity.

“We want to keep the mountains white here in Switzerland,” says Daniel Lüscher of myblueblanet. “That’s why we contacted I Am Pro Snow about three years ago, and asked if we could adapt it to Switzerland.”

The Swiss organization’s first partner resort was the trendy ski area of Laax in 2015, followed soon after by Arosa, Lenzerheide, St. Moritz and Saas-Fee. According to Lüschner, the first step for member resorts is to switch to 100% renewable energy—which due to hydropower, is already widespread in the Alps.

Resorts are also offering climate menus that generate fewer CO2 emissions. “Normally the emissions of a meal are 1.6 kilograms of CO2,” says Lüscher. “In the climate menu there are only 600 grams.”

Lüscher says that sustainability is a topic in Switzerland’s tourism industry, but it’s yet to make a breakthrough—for hotel managers, the main concern is still making money. He points out that the five I Am Pro Snow member resorts are now cooperating and sharing tips on best practices, something new in the Swiss tourism industry. One of the most exciting new plans includes a free train ticket for guests who stay for a week, cutting down on CO2 emissions from transportation. “We’re working on this initiative with a resort, and it will be implemented next season,” says Lüscher.

At Laax, the first resort to join the I am Pro Snow movement in 2015, a program called the Greenstyle Project had already been in place since 2010 with the goal of making operations more ecologically sound. Currently, electricity in Laax is provided by hydro and solar power from the local Flims Electric company. The resort has also installed solar panels on the roofs and sides of lift stations. The innovative approach has already earned the resort Swiss and European solar prizes. A local windfarm project on the Vorab Glacier is also in the works, and many of the resort’s guests arrive using the efficient year-round public transportation options.

According to Reto Fry, who’s led the Greenstyle Project since its inception, the resort re-evaluated the project in 2014, and set the ambitious new target of becoming a fully self-sufficient resort. However, when asked about the schedule for meeting that target, Fry estimates it will take “too long” at the current speed of progression. Another important task to fulfill is replacing all oil-heating systems by 2023. “We can’t just push initiatives that cost money. We also have to make them economically viable,” Fry cautions.

Fry says around 75% of the emissions generated by a resort are actually caused by transportation to the destination. Finding new ways to travel will be one of the many challenges of climate adjustment. “I have actually been looking for a travel agency offering sustainable holidays including renewable transportation, but I haven’t found any,” Fry concedes.

There is also a non-profit Greenstyle Foundation in Laax that operates on a crowd-sourcing principle and funds eco-projects in the area. Resort guests can participate and donate in the foundation. Resort employees can donate by voluntary salary deductions, which the company will then triple.

The resort of Laax, Switzerland has set ambitious sustainability goals including the use of 100% renewable energy, waste reduction and increased efficiency.

After the helicopter finished cutting down the snow-loaded tree branches, things soon seemed to return to normal in Koli. Getting electricity back in the surrounding province, however, took several days of clearing all the fallen trees from the electrical lines, and required the work of 200 people, eight wood harvesters and five helicopters. The local electricity company described the effort as the most massive in it’s history.

When I later talk with Veli Lyytikäinen, the manager of the Koli ski resort, he admits that the event probably happened due to the effects of climate change: “All the simulation models show increased precipitation for our area, and this season has been the second snowiest in our history.” According to Lyytikäinen, it took a month and a half to clear all the cross-country tracks of fallen trees, which tells something about the scale of the damage the resort had to deal with—something I witnessed personally during my trip on a ski touring mission with my father-in-law.

Lyytikäinen has witnessed firsthand how our thinking towards climate change has changed over the past decades. “I am a biologist, and I remember how twenty years ago we talked about how this will affect the tourism industry and people were joking about it a little bit,” He says. “Not anymore.”

Unlike twenty years ago, we now know that climate change is for real, and the outcome if we don’t take action soon enough, as the recent IPCC report suggests, looks grim—and not just regarding the future of our sport. Still, it’s good to remember that today we possess the necessary knowledge and technology to overcome the huge challenge that we are facing. All we need is the will to look at things from a new perspective, and the willingness to accept changes in our lifestyles and habits with the aim of minimizing our CO2 emissions.

Koli, Finland. Photo: Järvensivu